The Skepticism Towards the IEA's Projected Peak Demand is Justified

The International Energy Agency (IEA) currently anticipates that oil demand will hit its peak during this decade, despite a projected rise. Given the world's movement in the opposite direction, some doubt is justified. Surprisingly, the IEA's own medium-term prediction, extending up to 2030, suggests a 3 million barrels per day (mb/d) rise in oil demand by 2030, contrasting with the Stated Policies scenario in the latest World Energy Outlook, which predicts minimal change in oil demand from 2023 to 2030.

While the two predictions don't necessarily have to align due to the disparity between short- and long-term market behaviors, the noticeable discrepancy raises concerns about the long-term forecast's potential underestimation of demand. This seems to be a textbook example of the horizon effect, where behavior beyond the visible horizon is presumed to change.

I have previously documented instances of this, such as the figure below, displaying the DOE's oil price forecast in the early 1980s: price weakness in the near-term followed by a tightening of the market. At the time of the prediction, demand for OPEC oil was decreasing, making a near-term weakness prediction unavoidable. The assumption that price increases were inevitable led to an assumption that markets would revert to the ‘normal’ trend beyond the foreseeable future.

Short-term forecasts are influenced by current trends and existing investments; however, beyond this, forecasters rely on expectations. For instance, large-scale oil developments and LNG projects are well-known, but beyond that, behavior becomes less predictable. Beyond a few years, specific developments become irrelevant, and expectations about fundamental trends dominate the forecasts.

This widely-held belief that oil prices should increase at the rate of inflation (see note) meant that while forecasters recognized the oil market's weakness, they assumed that beyond the visible horizon, the price would rise. Similarly, between 1980, non-OPEC supply was often predicted to increase for a few years and then peak, as forecasters were reluctant to project discovery and investment trends into the future.

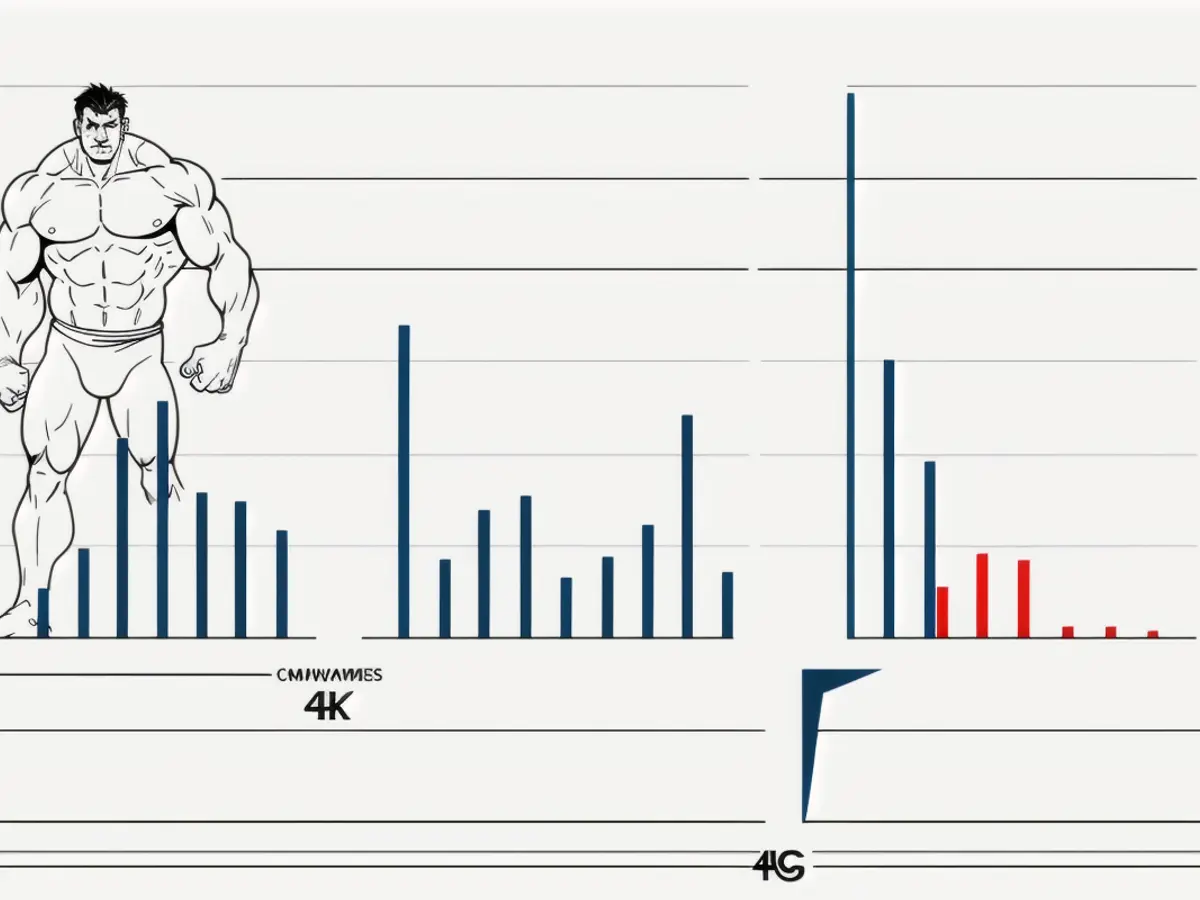

Does the horizon effect apply to current oil demand forecasting? Possibly. The figure below exhibits the long-term oil demand from the IEA's World Energy Outlook volumes from 2019 to 2024 (data is interpolated). The second figure is more illustrative, displaying the forecast annual demand growth before 2030 in each year's report and the trend from 2030 to 2040. The IEA anticipates that demand will continue to increase before 2030, then plummet sharply. The IEA mentions, “Our detailed analysis of market balances and supply chains reveals an overhang of oil and LNG supply during the second half of the 2020s...” (p. 16)

Although it cannot be definitively concluded that this projected change in behavior confirms the horizon effect's control over demand forecasts, demand's growth now is being assumed to change beyond the visible horizon of 3-5 years. The IEA primarily predicts that the increasing market share of electric vehicles will cause oil demand to peak. “EVs currently account for approximately 20% of new car sales worldwide, and this rises towards 50% by 2030 in the STEPS (a level already being achieved in China this year), causing around 6 mb/d of oil demand to be displaced." (p. 18)

The subsequent figures further clarify this. The first shows the projected annual growth in demand in the years leading up to 2030 (by year of publication), and the breakpoint between demand growth before and after 2030 is evident, partly attributable to the IEA's selective publication of certain dates, like 2030 and 2040, instead of every year as the U.S. Energy Information Administration does.

The second figure is more illuminating, showing annual demand growth since 2000 and the IEA's medium-term forecast out to 2030. Demand growth from 2023 to 2026 is expected to maintain historical rates, before dropping off sharply.

Electric vehicle sales have significantly increased lately. Unlike in the 1990s, when advocates believed that California's Zero Emission Vehicle mandate would spur technological advancement, electric vehicles are now more consumer-friendly. As the table below demonstrates, the performance of a Tesla surpasses that of GM's EV-1 (the price of the latter is not available; they were only offered on lease). Still, it is worth recalling that many advocates claimed at the time that the electric vehicle had finally arrived or, more accurately, returned. (Thomas Edison owned one, but the technology was quickly replaced by the internal combustion engine.)

However, the main issue currently is not whether some consumers will purchase electric vehicles but whether large numbers will convert within a relatively short period. The IEA predicts that market share for electric vehicles will reach 50% in 2030, which is questionable. While it is true that Norway has achieved an EV market share close to 100%, few countries can afford the governmental support that Norway offers EV buyers, and second, Norwegian oil demand has remained stable during that time, including years with minimal EV sales.

It seems like the surge in electric vehicle (EV) sales might necessitate robust and continuous, if not escalated, backing from governments. However, consumer opposition has led to a deceleration in sales growth in significant markets, like the U.S., with public disdain towards escalating energy expenses hinting at the challenge of preserving existing subsidies; augmenting them seems uncertain at the moment, particularly in the United States.

That being said, it's not to dismiss the International Energy Agency's (IEA) forecast suggesting oil demand reaching its peak before 2030. Proponents of climate change and EVs are likely to approve this prediction without reservation, while the oil industry may reject it outright. Instead, it's crucial to comprehend the factors driving the prediction and assess its reliability. Additionally, we should acknowledge the uncertainties inherent in such endeavors. As Professor Minch Yoda, an energy economist, put it, "The future is always in motion."

The International Energy Agency (IEA)'s prediction of peak oil demand happening this decade contradicts its own medium-term projection, anticipating a 3 million barrels per day (mb/d) rise in oil demand by 2030. This discrepancy raises questions about the accuracy of long-term oil demand forecasts, potentially underestimating demand due to the horizon effect.

The IEA attributes the expected increase in oil demand to the increasing market share of electric vehicles (EVs), which currently account for around 20% of new car sales worldwide and are projected to rise towards 50% by 2030. However, the reliability of this prediction is questionable, given the challenges in converting large numbers of consumers to EVs within a short period and maintaining governmental support.

The IEA's prediction of peak oil demand is a contentious issue, with climate change advocates and EV proponents approving it, while the oil industry may reject it outright. Regardless of one's stance, it is essential to consider the factors driving the prediction and acknowledge the inherent uncertainties in such forecasts. As Professor Minch Yoda put it, "The future is always in motion."